Careers Spotlight

|

|

By Mark Small, Berklee Class of '73 |

|

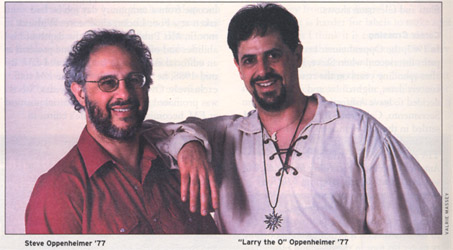

After separate odysseys, brothers Steve and Larry "the O" Oppenheimer have landed choice careers in the world of music technology. |

|

|

After finishing their studies, many alumni leave Berklee aiming for a career on the stage. After some time passes, a portion of them often migrate to different parts of the music industry and into careers they were unaware of before entering "the real world." Brothers Steve Oppenheimer '77 (a pianist) and Larry "the O" Oppenheimer '77 (a drummer) are cases in point. After years of playing professionally and moving around the nation and the music industry, both now occupy key posts in the high-tech quarters of the music business in San Francisco. Not surprisingly, as the brothers followed their individual paths, they have seen their educational and professional pursuits intersect at several points. Steve currently works for publishing giant Primedia Business Magazines and Media as editor in chief of Electronic Musician and Onstage magazines. Larry recently became audio director for Electronic Arts, the world's largest producer of electronic games. For the previous seven years, Larry was at LucasArts Entertainment, where he worked on the bestselling games Rebel Assault 2, Escape from Monkey Island, and Star Wars: Bounty Hunter. While their current positions require highly specialized skill sets, Steve and Larry readily testify that the education and experience they gained in the music industry and elsewhere qualified them for these unique positions. Lured into Music While honing his piano chops as a Berklee student, Steve had some choice encounters with jazz piano-greats. "I had this friend who knew a lot of jazz musicians in New York," Steve recalls. "She took me to meet Roland Hanna at his New York apartment. I ended up studying with him for a few days and sleeping on his couch. During the same trip, I met Nat Jones, who invited me to sit in with his trio at the Bottom Line. That experience was one of those that affects you deeply." After leaving Berklee in 1977, Steve freelanced as a keyboardist, arranger/composer, recording engineer, and sound designer. Soldering up a Storm Larry later earned an associate's degree in electrical engineering and computer science from the Lowell Institute School at MIT. In 1980, he founded Toys in the Attic (TIA), a music and technical services company that he still operates as a sideline. Under the moniker of TIA, Larry has undertaken a dizzying array of projects, including writing technical manuals, repairing and renting musical equipment, producing and engineering recordings, and doing sound and music editing for feature films and television shows. Career Crossing "For my birthday in 1987, Larry invited me to come down to San Francisco to go out to dinner and then to a Grateful Dead concert," Steve recalls. "On the way to the concert, we stopped at the Mix offices so Larry could pick up his check. He took me around and introduced me to a bunch of people including George Petersen, who at that time was the magazine's associate editor. I thought it seemed like a cool place to work. On my way out, I stopped to talk with one of the proofreaders. I looked over his work and started thinking that I'd be good at that kind of thing. Larry told me who to talk with about a job but otherwise stayed completely out of the process." Steve sent his resume to the magazine's general manager, who then invited him to take a proofreading test. Not only did Steve catch grammatical and punctuation errors, but he corrected technical mistakes that the author and editors hadn't realized were there. Steve was summarily offered a job as a freelance proofreader. Out of the Footlocker During his tenure, he has helped transform EM from what he calls "a small electronics hacker magazine" into a leading technical publication for musicians with personal studios. He facilitated the company's growth by recruiting an exceptional team of editors and freelance authors and by creating many of EM's file management and tracking systems and their editorial project-management systems. Additionally, Steve writes a monthly column, has penned numerous EM articles, coauthored and edited titles for EM Books, and was founding editor of EM's sister publications Onstage and Remix, as well as the annual Desktop Music Production Guide and Computer Music Product Guide. Digital Revolution |

Larry's business also grew with the flowering of digital technology. In addition to the previously mentioned projects that Larry (a.k.a. Toys in the Attic) undertook, he contracted with manufacturers such as Ensoniq, Opcode, Sonic Solutions, Zoom Corporation, Digidesign, and others to do product design consultation, copyright research, provide technical services, and more. In 1993, he took a full-time job as lead editor and operations manager for WaveGroup, a postproduction facility employing ADAT recorders and Pro Tools software. At WaveGroup, one of the many projects Larry undertook was the creation of the soundtrack for a television animation series called Bump in the Night. New Directions For the next seven-plus years, Larry served as sound-development supervisor at LucasArts. He handled a range of chores, including designing sound for games and assorted technical development jobs, contributing to several of the company's best-selling titles. The game field is intellectually stimulating and one that promises plenty of growth. "Working on games is exciting and a challenge," he says. "Games are becoming a bigger part of the entertainment industry. Internet gaming or multiplayer online games are starting to take off. The next generation, console platforms, is getting more powerful. This is a frontier, and there are very few of those around." Early this year, when Electronic Arts made him an offer he says he couldn't refuse, Larry left his post at LucasArts. As the Electronic Arts audio director, Larry has a role similar to that of an audio director in the film world. "Basically, I am responsible for everything that comes out of the speakers," he says. "Whether I create the sounds or direct the entire effort, there is a lot involved." Currently, he is working on the company's new James Bond game. Nonlinear Media While everyone's career path unfolds in its own unique way, the Oppenheimers have thoughts for those keeping an eye toward the horizon. Steve suggests that aspirants approach learning a new business the same way they did mastering their instrument. "First, learn how to write," he says. "A lot of people who want to write for EM know the tech side of things but can't write. When I came to this job, I spent an unbelievable amount of time in my office teaching myself about word processing, database programming, and copyediting. The editor job sometimes involves making a writer sound better than he or she actually is. But if that takes too much time and effort, we might as well just write the article ourselves. It is worthwhile to take classes in journalism or copyediting. If you were serious enough about music to spend hours a day in the practice room, understand that developing as a writer takes the same kind of commitment." Good Times for Tech-Oriented Musicians As for the future of their individual industries, Larry paints a rosy picture for the electronic-games business. "This field has exploded. Depending on who you work for, there can be money in it. I see a bright future for musicians and sound specialists in games." While Steve doesn't see the magazine business "exploding," he forecasts a steady future. "The publishing industry is not in the shape that Larry's business is in," he said. "People aren't reading as many books and magazines as they used to, and yet there are now more magazines out there than ever before. Magazines have been around a long time, and I don't think they are going away. There is something about a magazine that you can't get right now out of electronic media. Magazines are portable, you can take them with you and they are disposable when you finish reading them." When asked for the long view of the digital-music-technology revolution that has fired up each of their businesses, they agree that it is a great time for technologically adept musicians. "When I was at Berklee, there was the performance side of music and the recording side," says Steve. "You could specialize in one or the other, and some people did both. These days, if you don't record or have a home studio, you're missing out." "It used to be that there were plenty of performance venues but it was hard to get access to recording equipment," says Larry. "Now it the opposite. Decent-sounding recording equipment is affordable for musicians. The old revenue model for record companies is crumbling, and it's now harder for big labels to make money from recordings." "Yes," Steve chimes in, "it is harder for labels to make a lot of money, but I think it is easier to make money in general from recordings now. Every day at EM, I get CDs from people who are making a living selling their own independent recordings. You gotta love the possibilities for musicians living in the digital age." |

This article originally appeared in the Summer 2003 edition of Berklee Today magazine, a publication of the Berklee College of Music, and is reprinted with the permission of its publisher. |

|