ENGLONICS |

|

|

By K. Gordon Oppenheimer

|

|

|

English is really a very good language, despite the incomprehensibility of some of its grammar, spelling and pronunciation rules. It does not deserve the bad rap which it has been given and it most certainly does not deserve the cruel handling which it has endured over the centuries. Englishmen will not concede that the language spoken by Americans is English and they, unfortunately, are correct that the language is misused in ways that evoke disbelief and bring tears to the eyes of dedicated professors of English. It is not the purpose of this work, however, to catalog examples of the gross misuse---abuse is more descriptive---of the English language by Americans. For example, consider the following excerpt from A Civil Tongue, by Edwin Newman1 in which he recites an imaginary, but typical, conversation between the chancellor of the New York City schools and the coordinator of research in a state education department, based on actual conversations of these two educators: "What are you up to these days, {Chancellor}?" "I am effectuating economies. And you, Research Coordinator?" "I am reading summarizative descriptions of law and citizenship programs, but I fear that they will not be suitable for a dissemination program because of their lack of evaluative data and their requirement of professional law personnel." WHAT? "PROFESSIONAL law personnel", I take it, means lawyers, but the rest of this intellectual discourse eludes me. This type of jargon, however, is not the exclusive province of educators. There is also a sub-language known as "Police-ese" which is, predictably, the lingo used by the police to describe an event. For example, the man didn't get out of his car---"The subject exited the vehicle". The man wasn't armed: The individual was armed with a weapon." (What else could he be armed with if not a weapon?) IT would be just to visit upon those who would abuse our modern language "a punishment to fit the crime". What immediately comes to mind is that they should be compelled to learn and use properly the Old English of Beowulf and Chaucer! We could call it "Beowonics" or, if you prefer, "Chausonics"! Even scholars who enjoy English literature tend to avoid Old English; others profess a genuine affection for it. To each his own! Nevertheless, it would be instructive to examine an excerpt from Beowulf to determine whether we want to institute a program of study of "Beowonics" in order to foster an appreciation of our simple modern language. This is the lingual burden which, undoubtably, induced our English fore bearers to emigrate to the Colonies. "Heald2 pu nu, hruse, nu hæleõ

ne mostan, "Hold them now, Earth, now hand of

man cannot ABOUT eight centuries after Beowulf and Chaucer, the language took a turn for the better and another, less tortured form, evolved. "Scots" is a northern English dialect used by the Scottish peasantry. This dialect was used extensively by Robert Burns and we shall, for logical reasons, call the study of it---what else?---"Scotonics". An excellent example of the use of "Scots" is found in Burns' well-known "To a Mouse on Turning Her Up in her Nest With the Plow". written in 1785. The poem is set out below in dialect, followed by its modern English rendition. The reader should not permit himself or herself to be distracted by the vision of an apparently normal man talking’Äînay, apologizing to’Äîa mouse!

|

Wee, sleekit, cow'rin', tim'rous beastie, Small, sleek, cowering, frightened beast, AND there it is! Notice that, unlike Beowulf and Chaucer, you can read, understand and enjoy the Scottish dialect which, with the exception of a word here and there, requires no translation or explanation. To illustrate this simplicity, we will consider a few more lines from the same poem without referring to the dictionary which, until now, we have had closely at hand. WARNING! Do not attempt to run this poem through a spell-checker! I doubt na, whiles, but thou may thieve, UPON further reflection, perhaps it would be better to ignore the preceding paragraph which points out so vividly the ease with which "Scots" can be read and understood. "Scots" would appear to be an outstanding candidate for addition to the mandatory study and use which will be prescribed for those who persist in distorting the English tongue. FINALLY, there is that curious form of English which is, perhaps, best referred to as "Biblical" English. Surely the reader must know what's coming. Yes, indeed. We will call the study of Biblical English "Biblionics." It should be noted that, unlike other forms of English, Biblical English is limited in its usage to clergymen and religious works. Let us look at the 23rd psalm for an example of that use. The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not want. The Lord is my shepherd; I will not need

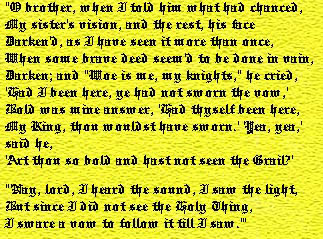

anything. THERE is yet another form which is closely akin to Biblical English and that is the language of the Middle Ages. A short excerpt from Tennyson's Idylls of the King4 should suffice to illustrate the point: "O brother, when I told him what

had chanced,

THIS concludes our review of the subjects to be taught under the rubric "Englonics," save for one form which can be used to increase the complexity of the written English word without significantly adding to our ability to read and write the English language. The following paragraph shows us what happens when we combine the language of the Middle Ages with Old English script:

|

Notes: |

|